THE CRIMINAL PSYCHOLOGY

Literally, criminal psychology should be that branch of psychology that deals with crime and not merely the psychopathology of criminals and the study of the criminal mind. However, this literal definition is not the psychology required by the criminalist. The “Founding Father” of criminal profiling, Hans Gross, considered criminal psychology as pure research and called for the objective use and examination of evidence. (Criminal Psychology by Hans Gross).

The most common definition of criminal psychology is “the branch of psychology which investigates the psychology of crime with particular reference to the personality factors of the criminal.” However, as Bartol & Bartol (2004) pointed out in recent years (at least since the early 1990s) that there was a movement away from a focus on personality factors towards “developmental” factors. Developmental theory is a subfield of criminology (Loeber & LeBlanc 1990) and a subfield of psychology (Manaster 1977) sometimes known as “child” or “adolescent” psychology.

Criminal psychologists seek to understand the motivations of criminals and develop a psychological profile to understand or apprehend them. They examine individual criminal behaviors and diagnose any mental health conditions. They frequently step into the courtroom to provide expert testimony.

Developmental theory is about normal human development or growing up. It looks for the causes of crime in the complex mix or interaction of various childhood cognitive deficits (e.g., low IQ, attention deficit disorder, conduct problems, cognitive “scripts”) with various situational or contextual handicaps (e.g., school failure, peer rejection, parental abuse or neglect, and gender/ethnic discrimination).

Within the field of criminology, the developmental theory is closely related to “general” theory (Gottfredson & Hirschi 1990) although the difference is that general theory implies a policy of selective incapacitation (wicked people exist and all you can do is lock them away) while developmental theory looks for intervention opportunities (e.g.tipping and turning points, desistance, life-course changes, pathways).

The appeal of criminal psychology, as it is presently dominated by the developmental perspective, has the same appeal as most psychodynamic psychology in that it seems to offer all the answers — that any criminal, no matter how bad, can be rehabilitated or reformed — and that any delinquent, no matter how bad, can be saved from a lifetime of crime.

However, it should be said that de-emphasizing the personality components (as most developmental theories do) has resulted in good headway toward “theory-driven, culture-sensitive, and gender-related” interventions, and that is no small feat, considering that forensic psychologists who work in criminal psychology often have to face significant multicultural and multiethnic challenges. (This is in case of racial crimes and terrorism)

First, however, it is important to understand why theory and typology are important in criminal psychology. In the understanding of criminal behavior, we take a look again at the THEORIES OF CRIME CAUSATION that we learned in FUNDAMENTALS OR BASIC OF CRIMINOLOGY in order to see the nature of the person’s behavior in relation to criminality. This is the only way for a criminalist, criminal psychologist, and criminologist to understand well the reason why a man becomes a criminal.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL APPROACH TO FACTORS AND CAUSES (OF CRIME AND DELINQUENCY)

Two or three assumptions make up the factual foundations for developmental approaches to crime and delinquency.

-

- (One) The spectrum of what we call criminal behavior is extremely wide with a range of behavior that varies from minor offenses to serious offenses. Criminal behavior is so wide-ranging because forms of it are so easy to commit or because crime is so prevalent in our society that in almost all socioeconomic groups, crime exists, and some of what we call delinquency may very well be a “normal part” of adolescent development.

- (Two) Even though sociological, psychological, and legal definitions of crime may seem different at times, there is considerable overlap between all the definitional approaches. This overlap or common ground is that the most troublesome, inappropriate, offensive, or “signature” criminals are those who seem to be following a lifelong career of crime despite society’s best efforts at informal and formal control.

There is therefore some value in looking at crime and delinquency from a lifespan, life course, lifelong, career, pathway, or developmental perspective.

Using the above assumption, start with your brainstorming with your group and try to answer these two questions:

-

- If WE “developmentally” GROW RIGHTEOUSLY A CHILD” would you think the assumption that CRIME IS A NORMAL PART OF ADOLESCENCE IS CORRECT whatever the socio-economic status of the society has? (Tagalog Version: Kung may katotohanan na kapag pinalaki natin ang bata na maayos, totoo kaya ang pagpapalagay na ang KRIMEN AY NORMAL LALO NA SA PANAHON NG PAGBIBINATA, ano mang uri ng kalagayan ng sosyedad meron ang isang lugar)

- What really pulls down a MAN IN HIS CRIMINAL ACTIVITY, that despite whether we have poor or sound definitions of the word CRIMES AND THE EFFORT OF THE SOCIETY TO REPEL IT, why there are still criminal who are troublesome, inappropriate, offensive, or signature criminals that may last throughout life in their career. (Tagalog Version: Ano kaya talaga ang humihila sa TAO SA KANYANG PAGIGING KRIMINAL, sa kabila ng alam nila kung ano ang KRIMEN ayon sa kahulugan nito maging simple man ang kahulugan o malalim AT BASE NA RIN SA PAGSISIKAP NG PAMAYANAN NA MASUGPO ITO, bakit may mga kriminal pa rin na masyadong magulo, marahas, hindi karapat-dapat at nakakapinsala, at nananatili sa isang tao habambuhay)

What you are analyzing now as a question and at the same time takeaways on this topic is a practice on how to profile both man and society psychologically and criminally. By focusing your attention on the above question, try also to consider and be able to connect some factors that are precursors for the criminality of man by reading further our literature below. You can use that as a basis in explaining criminal psychology.

In most cases, the causes of crime are likely to be multiple and complex involving mysterious “interaction effects” which are combinations of relatively minor influences by themselves. For example, the impact of being male (gender) and being exposed to violent entertainment on TV (exposure) may by themselves, be relatively minor influences. However, when both are combined (gender multiplied by exposure), the combination may produce a “mental aberration” which we might call a “male-dominated, media-driven” violence fantasy. There are hundreds of these kinds of interaction effects that are possible.

A forensic psychologist is most likely to tread these grounds at one of two points in the criminal justice system (1) the front end, during prosecution, and (2) the back end, during sentencing. There are some crimes, in order to be successfully prosecuted, that requires proving that a person must have known what they were doing at the time. The phrase “must have known what they were doing at the time” is known as the concept of intent or in legal terms as the concept of mens rea. In sociological circles, mens rea is the concept of responsibility and in criminal justice circles, it is the concept of culpability [see Lecture on Fundamentals of Criminal Law – both law and science wanted to know and learn whether they are AWARE of what they are doing].

Forensic psychologists are expected to be experts at mens rea or the degree of guilt of the various states of mind. This is a big challenge but no more demanding than what forensic psychologists are often called upon to do at the back end of the justice system. In reality, they conduct assessments of the “redeemability” or rehabilitation potential of a defendant who faces afflictive penalty or capital punishment because of their characterization as a “psychopath” or the like which was made an aggravating factor at their sentencing hearing. As Bartol & Bartol (2004) put it, a diagnosis of psychopathy is the “kiss of death” at capital sentencing.

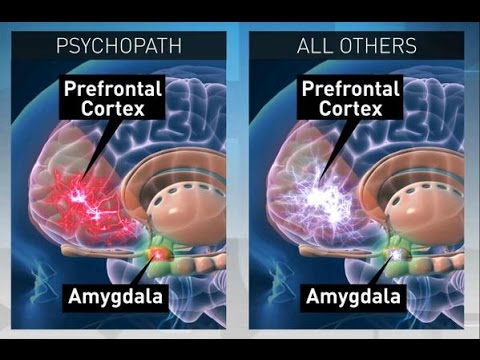

In today’s criminology, the concern over the mind is becoming more dynamic that even looking at the “STATE OF BRAIN” becomes an interest, and this is another criminological enterprise, the “NUEROCRIMINOLOGY.

On the one hand, there are so-called general theories of crime (Gottfredson & Hirschi 1990) which are sometimes referred to as “persistent heterogeneity” theses or paradigms (Nagin & Farrington 1992). These paradigms postulate that certain personality characteristics (such as lack of self-control) are so enduring and stable over time that some people are practically “destined” to a life of crime without hope of reformation. On the other hand, there are age-graded life-course theories (Sampson & Laub 1993), sometimes referred to as “state dependence” or “desistence” models or paradigms (Nagin & Paternoster 1991; Tracy & Kempf-Leonard 1996) which postulated that certain turning points in life or changes in circumstances (such as a job or marriage) sometimes lead to exiting, or desisting, from a career in crime.

Regarding whether or not any form of known treatment or intervention works to turn people away from a life of crime, the consensus of at least the clinical psychology literature is that “untreatability” statements are unwarranted (Salekin 2002) and that tough customers, like psychopaths, may simply need bigger “doses” of treatment. (In fact in the picture above showing a brain of a normal person and a psychopath is a BIG QUESTION as to whether can WE FIX THE BRAIN of these people!

(Read also and download the DEVELOPMENT OF CHILD TOWARDS CRIME AND DELINQUENCY and be able to read it) CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD

We will continue……

Next are all about

Abnormality and Mental Deficiency